AI technologies promise to affect nearly every aspect of our lives.1

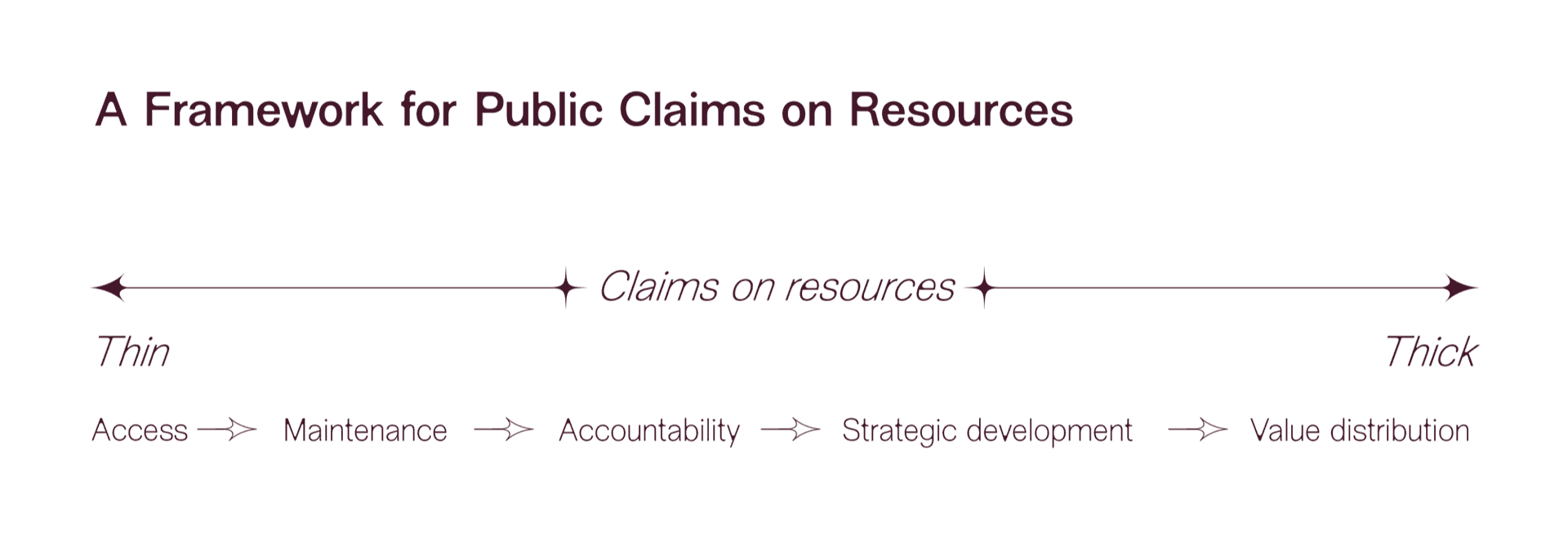

Within complex innovation systems both public and private investments flow into research and development. Instead of understanding ‘public’ and ‘private’ as binary conditions attached to specific types of intermediaries (i.e. state versus market actors), FAE proposes to regard the notion of publicness as a spectrum on which the terms of public agency are negotiated, ranging from ‘thin’ to ‘thick’. ‘Thick’ public governance might apply to state-run assets funded by taxes, while ‘thin’ publicness could be obtained when/where infrastructures are freely accessible to the public but are privately owned. Between these extremes, frameworks such as commoning could be deployed to pool resources offering greater access and maintenance buy-in.4

Today’s AI is constituted through an entanglement of resources and

infrastructures, each layer possessing its own context and openings for

incorporating publicness into its design. What follows is the mapping of

entanglements through AI’s technical stack, consisting of seven hierarchical

layers organised in two tiers. The ‘hardware’ tier which provides the physical

material and machinery by means of natural resource, server networks and

compute layers. These enable the transfer and processing of information in the

'software', from the data layer, to the model, network protocols and

application layers. By zooming in on the stack layers, the interdependence

between industry, states, non-governmental organisations, academia, and the

many publics that are implicated in the creation and adoption of AI can be

understood. Highlighting the fact that ‘public AI’ is not just a speculative

category, but a reality that requires ongoing development and support.9

Application Layer

Applications in the context of this AI stack are software products that utilise machine learning models as a core part of their capability; for example, content creation services such as Stable Diffusion, ChatGPT, or Suno.ai. Other present-day applications include virtual assistants (e.g. Apple’s Siri), recommendation systems (e.g. those used by Netflix), developer tools for writing code (e.g. GitHub’s CoPilot), speech and language recognition tools (e.g. Google Translate), biometric identification technology (e.g. fingerprint recognition AppLock), computer sensing and simulation systems (e.g. as those operated by driverless vehicles such as CARLA), search engines (e.g. Google Search and Bing), and others.

While the release of ChatGPT in November 2022 captured the public’s imagination, the history of applications that use different underlying AI capabilities (or precursors to AI) spans decades.10

Application development is underpinned by a robust ecosystem of open research and code sharing. The development of applications relies on platforms such as GitHub (for code), and HuggingFace (for machine learning models and datasets). Applications can be patented (e.g. Spotify). In the US and Europe, applications are subject to a voluntary code of practice, which extends to application providers in general.13

Network Protocols Layer

Network protocols define the rules for how data is transmitted and received over a network, enabling AI applications to communicate efficiently with each other, with data sources, with AI models, and with end-users.

Hypertext Transfer Protocol (HTTP) is the open data communication protocol underlying the World Wide Web. Its specifications standardise the exchange of information; they are publicly available and can be used by anyone.15

An Application Programming Interface (API), on the other hand, is a set of tools that enables the exchange of data and functionality between platforms, and integrations between different systems and devices. In AI applications, APIs are often used to access the capabilities of AI models, without interacting with the model itself, at a fee (e.g. enterprise-grade Gemini and ChatGPT Enterprise).

Model Layer

A machine learning model is a computer programme. In contrast to conventional programming, it is not manually defined through a sequence of instructions. Instead, the process of defining the computer programme is automated by means of algorithms that find patterns in large quantities of exemplary data.17

Building efforts have consolidated around just a few foundation models within corporate, or privately-controlled, contexts due to the massive investments that they require.21

Whether open source or closed, not all model-makers reveal the contents of their training data, and it is believed that much of it is protected by copyright. Consequently, these leading AI organisations are confronting legal challenges that have yet to result in new laws.26

Data Layer

Models require high quality data for training and fine-tuning.30

High profile lawsuits brought against companies including OpenAI, Microsoft, Stability AI, and Midjourney allege that their models infringe on copyrighted material in the training of their models.35

Compute Layer

Data-driven machine learning algorithms are reliant on high-performance computing. Graphics processing units (GPUs) are semiconductor chips originally designed for 3D graphics, but their competency in performing complex mathematical calculations at high speeds has made them hardware that is fundamental to AI systems in order for models to be trained quickly and at scale.40

Because of high demand, intense global competition and geopolitical tensions have emerged surrounding the semiconductor industry; nations are vying for dominance in manufacturing, design, and supply chain control. In the past three years, particularly in response to Taiwan’s geopolitical status as the leading global chip producer, governments in the US, the EU, and the UK have pushed to support national semiconductor manufacturing, research, and development through new policy positions, legislation, and by providing financial incentives. Generally, investment by outside actors in national or enterprise computing projects is regarded now as a matter of national security and global competition.41

As opposed to applications, network protocols, and small-scale models, the computing costs of foundational models means that GPUs are less accessible for small-scale entities or open innovation, raising questions about enclosure. It is a resource that has consolidated around a few key companies that service both the market and government needs.

Server Networks Layer

Server networks, otherwise known as ‘clouds’, are clusters of computers that store data, run software such as AI models, and provide access to both data and models via APIs and communication protocols.43

Natural Resources Layer

Control over natural resources including oil, gas, and coal has shaped modern society, creating massive levels of wealth, and establishing new regulatory regimes, while simultaneously accelerating environmental breakdown and laying the foundation for the technological developments of the 20th and 21st centuries. In centuries past, the search for and sequestration of natural resources provided the foundation of colonial projects. Today, control over rare earth metals, integral to both the global rollout of renewable energy and the mass expansion of AI, will define relationships between countries and companies who have access to rare metal wealth and those who do not.

The natural resources required for AI can be broadly grouped under the headings of materials and energy. Materials e.g. silicon, gold, silver, palladium, and lithium are necessary for the fabrication of chips, servers, cables, and batteries. Energy from renewable sources (wind, solar, hydro), fossil fuels (oil, gas, coal), and nuclear reactions (fission and fusion) power the data centres, server networks, and computing operations, as well as their cooling systems.

From publicly owned oil companies such as Norway’s Equinor, to fully privatised water companies in the UK such as Thames Water, governance of natural resources across the Western world varies by location and resource. Much attention in recent years has been focused on establishing democratically, or at least more publicly, accountable energy systems across Europe with an accompanying shift away from oil, gas and coal towards renewables.45

Footnotes

-

Many groups are working to define ideas of public AI; they include: The Public AI Network, Public AI White Paper (2024) [link]; Collective Intelligence Project and The Alan Turing Institute amonst others. FAE4 draws on ideas from across these frameworks. We also use the term ‘public’ following John Dewey’s conception of the term in The Public and Its Problems (1927). ↩

-

This includes much of academia as well as non-profit orgs committed to stewarding the commons such as Internet Archive [link] and Arxiv [link]. ↩

-

Elinor Ostrom, Governing the commons (1990). ↩

-

Mariana Mazzucato, Public Purpose: Industrial Policy’s Comeback and Government’s Role in Shared Prosperity, (2021). ↩

-

UK AI Research Resource dubbed Isambard-AI will be one of Europe’s most powerful supercomputers. The new facility will serve as a national resource for researchers and industry experts spearheading AI innovation and scientific discovery. An unprecedented £225m investment has been allotted to create UK's most powerful supercomputer in Bristol (2023) [link]. ↩

-

These include organisations such as The Alan Turing Institute, Aapti Institute and Omydiar Network. ↩

-

An endeavour can be understood as ‘public’ when it is ‘in service of society and not industry or government’. See Jürgen Habermas, The Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere (1991). ↩

-

OpenAI, Introducing ChatGPT [link]; William van Melle, MYCIN: a knowledge-based consultation program for infectious disease diagnosis (1978) [link]; Bruce T. Lowerre, The HARPY Speech Recognition System (1976) [link]; Feng-hsiung Hsu, Behind Deep Blue: Building the Computer that Defeated the World Chess Champion (2002). ↩

-

Tammy Lovell, NHS rolls out AI tool which detects heart disease in 20 seconds (2022) [link]. ↩

-

In France, tax authorities used proprietary software developed by Google to identify undeclared tax revenue. See* Undeclared pools in France uncovered by AI technology* [link]. ↩

-

In 2022, the UK government set out a voluntary code of practice that includes better reporting of software vulnerabilities and more transparency for users regarding the privacy and security of apps available in all app stores. See New rules for apps to boost consumer security and privacy [link]. ↩

-

In New York State, automated hiring apps are subject to bias testing. NYC Consumer and Worker Protection, See Automated Employment Decision Tools: Frequently Asked Questions (2023) [link]. ↩

-

Rishi Bommasani et al., On the Opportunities and Risks of Foundation Models (2021) [link]. ↩

-

Foundation models generally refer to transformer architecture trained on huge amounts of data and use transfer learning to perform general purpose tasks that can then be further fine-tuned into skills such as text synthesis, image manipulation, or audio generation. See Elliot Jones , Explainer: What is a foundation model? (2023) [link]. Rishi Bommasani et al.,_ On the Opportunities and Risks of Foundation Models _(2021) [link]. ↩

-

See OpenAI’s GPT-4 [link]; Google’s Gemini [link]; Meta’s Llama 2 [link] and Mistral AI [link]. ↩

-

Rishi Bommasani, et al., On the Opportunities and Risks of Foundation Models (2021) [link]. ↩

-

Harsha Nori, Can Generalist Foundation Models Outcompete Special-Purpose Tuning? Case Study in Medicine (2023) [link]. ↩

-

Yi Tay, Training Great LLMs Entirely from Ground Up in the Wilderness as a Startup (2024) [link]. ↩

-

Billy Perrigo, Yann LeCun On How An Open Source Approach Could Shape AI (2024) [link]. ↩

-

Stable Diffusion is a model by UK-based AI company Stability AI, with open source code and weights [link]. ↩

-

See Tim Bradshaw and Joe Miller, New York Times sues Microsoft and OpenAI in copyright case (2023) [link]. ↩

-

For example, an investigation by The Atlantic in August of 2023 revealed that Meta partially trained its extensive language model using a dataset named Books3, which includes over 170,000 books that are either unauthorised copies or otherwise protected under copyright rules. Alex Reisner, _Revealed: The Authors Whose Pirated Books Are Powering Generative AI _(2023) [link]. ↩

-

Because their rise has been so meteoric, the attempts to regulate models are still in their infancy, with suggested measures under development in the EU, US, China, and the African Union. In the UK, the Frontier AI Taskforce, is a research team within the government to evaluate risks. In the House of Lords, a draft Artificial Intelligence (Regulation) Bill has been put forth. See Robert Hart, White House Unveils ‘Sweeping’ AI Strategy As Biden Pushes For Transparency And Safety (2023) [link] and Artificial Intelligence (Regulation) Bill (2023) [link]. ↩

-

High-quality data is accurate, complete, reliable, and relevant information for its intended use in operations, decision-making, analysis, or processing. See Maria Priestley et al., A Survey of Data Quality Requirements That Matter in ML Development Pipelines (2023). [link]. ↩

-

Jia Deng et al., ImageNet: A Large-Scale Hierarchical Image Database (2009) [link]. ↩

-

Baack, Stefan, and Mozilla Insights, Training Data for the Price of a Sandwich: Common Crawl’s Impact on Generative AI (2024) [link]. ↩

-

USA cases: Tremblay v OpenAI (consolidated with Silverman v OpenAI and Chabon v OpenAI), 2023; Alter v OpenAI and Microsoft (consolidated with Authors Guild & ors v OpenAI), 2023; Basbanes & Ngagoyeanes v Microsoft and OpenAI, 2024; The New York Times v Microsoft and OpenAI, 2023; Chabon & ors v Meta Platforms, Inc., 2023; Kadrey v Meta Platforms, Inc., 2023; Andersen v Stability AI, 2023; Getty Images v Stability AI, 2023; Huckabee & ors v Meta, Bloomberg, Microsoft and The EleutherAI Institute, 2023; J.Doe 1 and J.Doe 2 v GitHub, Microsoft and OpenAI, 2022; Concord Music Group & ors v Anthropic PBC, 2023; Thomson Reuters v Ross Intelligence, 2023. UK: Getty Images v Stability AI, 2023. ↩

-

LAION, Laion-5b: A New Era Of Open Large-Scale Multi-Modal Datasets (2022) [link]. ↩

-

In the UK, Health Data Research UK is a portal that enables access to health data to enable research and development. See Health Data Research UK [link]. ↩

-

Other public services, e.g. public transport or postal services, also create data that could be used to improve the services they provide. Over the last several years, ‘data dignity’ campaigners and associated organisations have been working to prototype new public governance models for data protection including data trusts and cooperatives. See RadicalxChange [link], Aapti Institute [link], Open Data Institute [link], Data Empowerment Fund [link], and Data Trusts Initiative [link]. ↩

-

Significant increases in computational power since 2016, thanks to advancements by Nvidia, AMD, Intel, and Qualcomm, have enabled the training of larger and more complex AI systems [link]. ↩

-

Paresh Dave, OpenAI Agreed to Buy $51 Million of AI Chips From a Startup Backed by CEO Sam Altman (2023) [link]. ↩

-

Anna Tong et al., _Exclusive: ChatGPT-owner OpenAI is exploring making its own AI chips _(2023) [link]. ↩

-

While it is true that server networks also use computing units (e.g. CPUs) to communicate, dividing the server network and compute layers in this AI tech stack allows for clarity in terms of the unique infrastructural and governance issues of each respective layer. ↩

-

Debbie Weinstein, Our $1 billion investment in a new UK data centre (2024) [link]. ↩

-

TUC, Public ownership of clean power: lower bills, climate action, decent jobs (2022) [link]. ↩

-

Jake Simms and Andy Whitmore, with contributions from Kim Pratt, Unearthing injustice: A global approach to transition minerals (2023) [link]. ↩